Custom Search

|

|

| sails |

| plans |

| epoxy |

| rope/line |

| hardware |

| canoe/Kayak |

| sailmaking |

| materials |

| models |

| media |

| tools |

| gear |

| join |

| home |

| indexes |

| classifieds |

| calendar |

| archives |

| about |

| links |

| Join Duckworks Get free newsletter Comment on articles CLICK HERE |

|

|

| CHASING GHOSTS IN THE GRAND CANYON |

| A COLORADO RIVER RUN Sunday, March 25 Just before 6:00 a.m. and it's starting to get light. We're camped at a place called Tatahatso, a small sandy beach tucked in a bend at river left, 38 miles downriver from our put-in at Lee's Ferry. Above us a huge bowl-shaped ampitheater is carved into the cliffs overhead--a short steep slope and a few moves along a narrow ledge gets you there. Yesterday Greg Hatten and I climbed up there, and scrambled further up to the lip of the cliffs overlooking the camp kitchen. A loooong way down. My memories of Grand Canyon before this trip date from a road trip with my parents and grandparents when I was six years old: a stop in a gift shop, an hour or two looking down from overlooks along the rim, and a short hike partway down the mule trail from the visitor center. Seeing it from the river is another world. It's a deep narrow canyon here at river level, even miles above the inner gorge. Tall red and gray and brown cliffs drop from the sky to the river's edge. Weird pinnacles and hoodoos line ridges hundreds of feet above. The river snakes its way through bend after bend, and each turn reveals a new variation of rock and sky: natural bridges and arches, huge caves, abandoned mine shafts, hanging canyons and dry pourovers that would quickly become hammering waterfalls in a flash flood. At night only a narrow slice of sky is visible, studded with starts brighter than you'd see from any city. I'm beginning to think I'll be putting my name in for a river permit of my own for next year. Today will be another easy day, Tom Martin tells us at our morning briefing. No big rapids to run, and the wind looks like it should be backing off. We'll stop at President Harding Rapid to look for the only campsite from Moulty Fulmer and Pat Reilly's 1957 high water trip that Tom Martin and Dave Mortenson have not been able to find yet. With the other campsites they had photos to work with. And although they know Fulmer and Reilly camped above this rapid, there are no photos to work with. "We'll be looking for a very tiny needle in a very big haystack," Tom says. Indeed. President Harding Rapid The river winds generally southward for several miles out of Tatahatsu before it sweeps into an S-curve six miles long. President Harding rapid sits in the middle of the S, just past the remnants of an incredible wooden bridge built high up the limestone wall on river right: Anasazi Bridge, part of the ancient network of trails that the Canyon's former inhabitants built centuries ago. I can't even see a way up to the bridge, and they used it as a roadway. After we run President Harding Rapid (an easy drop), we pull in for lunch and a bit of digging around to see if we can find any evidence of Fulmer and Reilly's camp. Tom Martin has a pretty good idea where the water level was in 1957--you can see the driftwood from that year high above today's water levels--and a few of us wander around looking for tin cans or fire rings. I find a mess of driftwood caught in a dead mesquite tree. Buried inside is a blue bottle, with a graduated scale running up one side. Nearby is a chunk of milled lumber with a bent rusty nail in it. I call Tom over--would Fulmer and Reilly have used a glass bottle? No, Tom decides. He thinks the stash of driftwood I discovered is probably from the 1921 flood (a nail from the similar 1880s flood would have been square, not round), which crested about 1,000 cubic feet per second higher than it did on Fulmer and Reilly's 1957 trip. But that means we're close--the water would have only been about a foot or two lower in 1957. Fulmer and Reilly's camp would be at almost this same elevation. With any luck, contouring along at this level above the rapid will eventually turn up some hard evidence. But not today--we've got some miles to do yet. I tuck the bottle back in the driftwood where I found it and we head back to the boats. But I can't help stopping at each likely flat rock or camping spot along the way, hoping to be the one to discover the Neither does the Canyon. Above Harding Rapid lies the grave of Peter Hansbrough, who drowned in Grand Canyon in 1889. A year later, Robert Stanton's survey crew found his body here and buried it at the base of the cliffs above the rapids, carving his initials (PMH) into the cliff face where they can still be seen today. Just a couple of minutes further walk upriver from the Hansbrough inscription is another grave, a Boy Scout who drowned in Glen Canyon in 1956. Fulmer and Reilly aren't the only ghosts here. Wind After Harding Rapid, the canyon turns westward to finish its giant S curve. Westward, into a stiff west wind. Soon our little fleet is spread out over a long stretch of river as we row into it. At one point I stop rowing in the middle of a fast-flowing ripple and the wind pushes my raft several yards upstream. It's a hellaciously long row to the next bend, where the headwind grows even stronger, pouring up the canyon. We pull in to regroup at a camp called Dinosaur at mile 50, then finish the day with a couple more tough miles upwind, camping for the night at Little Nankoweap, 52 miles downriver from Lee's Ferry. Elementary physics again--air forced through a narrow slot (a canyon, for example) will speed up. Up is the Had I known physics was going to be so important later in life, I might have paid a little more attention in Mr. Oldenburg's class.

When Fulmer and Reilly rowed through here, they found much more difficult conditions. Tom Martin's forthcoming book, Big Water Little Boats, puts it this way:

(from Big Water Little Boats by Tom Martin, available at bigwaterlittleboats.com)

But if there's anything worse than rowing an overloaded raft into a stiff headwind--20-25 knots, I'd guess--it's unloading piles and piles of gear from the boats and setting up camp. Again, physics: work = force x distance. It takes a lot of force to hoist all that gear, and our campsite is 25 feet above the water. And the wind hasn't let up either. Every few minutes a particularly energetic gust throws a fine haze of beach sand over everything. I'm on dinner crew tonight, along with Crystal, another first-time rower, and Dave Mortenson. After a lot of scrambling from boat to boat looking for tonight's food, we finally manage to set up the camp kitchen and serve up a respectable meal of hamburgers, brats, stir fry, and French onion soup--with fresh tomatoes, avocados, sliced onions, ketchup, mustard, bacon bits, Swiss cheese, buns, and cookies for dessert. No one complains about the sand. Saturday, March 24 A fairly uneventful day completing our run through a series of 10 rapids called the Roaring Twenties, stretching from just past river mile 20 to river mile 29. Short easy runs that we don't bother to scout. Along the way we stop at Vasey's Paradise to refill our water supply. Here a small waterfall drops directly from a limestone cliff far above. It's a simple task to haul our 5-gallon water cans up to a convenient little pourover and fill up. Pure water, filtered by hundreds of feet of limestone filter. We drink it as is. Later in the day we stop at Redwall Cavern. Redwall Cavern Redwall Cavern is a huge low-arching cavern mouth on river left. That is, it looks low until you notice the people standing on its sandy floor. Tiny people, with tiny boats pulled up on the beach below. Redwall Cavern is immense. I snap a couple of photos as I pull in from upriver, but I'm not a good enough photographer to do the place justice. Tom Martin and some of the others match photos from earlier trips here while I simply lie back on the sand and stare out the cavern's mouth at the river and the cliffs beyond. You could easily play a football game inside the huge cave, complete with hail Mary passes arching high overhead. But when Pat Reilly and Moulty Fulmer passed Redwall Cavern in 1957, much of it was underwater.

In the summer high season, about 180 people launch from Lee's Ferry on Grand Canyon river trips each day, and you wouldn't find Redwall Cavern empty when you got there. In fact, except for one other party of rafters who passed us because we stopped to film and rematch photos, we've seen no one besides ourselves on the river. Camp Life "I always say preparing for a Grand Canyon trip is Class VI logistics," Tom Martin told me when I arrived in Flagstaff. Now that we've been on the river a few days I'm beginning to understand what he means. Our arrival in camp each night sees a flurry of unloading boats and hauling an incredible amount of stuff up onto the beach: tables, tarps, kitchen boxes, food boxes, boxes full of dishes and bowls and silverware, stoves, more food boxes, charcoal, fresh produce (each raft carries a huge cooler filled with blocks of ice and meat and produce and who knows what--each cooler is big enough to hold a corpse, even without dismembering it first), the groover and its supply box, a camp chair for each person, stoves, water jugs, propane canisters, batteries to charge cameras and laptops, a complex and somewhat Rube Goldbergian hydro generator to recharge the batteries, camera gear and tripods for our videographer, and heaps of dry bags filled with tents, clothes, and personal gear. I'm probably leaving a bunch of stuff out. An eighteen-foot raft will hold a whole lot of gear, and we have five rafts on the trip (though one, it's true, is only a sixteen-footer). Once the boats are unloaded, anyone not on duty for the night finds a spot to set up their tent or roll out their sleeping bags. But some of us are working each night; fifteen of the sixteen people on the trip are divided into three-person work teams (the sixteenth person, nine-year-old Natalie, has homework to do each night instead). One team sets up the groover when we arrive at camp, and packs it up again to load in the morning. Another team cooks dinner (what we Midwesterners would call supper) and then prepares breakfast and lunch the next day. Yet another team washes the dishes after dinner, and again at breakfast the next day.Since there are five teams and only three duties, that means there are two teams off each night. So the order of duties is: groover set-up one night, cook dinner the It's enough stuff to make you feel like you're on an EXPEDITION. Which might be the point, I suppose. Apparently "light and fast" is not a philosophy that's caught on with river runners. Which has a bright side, after all: it's harder for a heavy boat to be flipped by a big wave. Still, I wonder what Pat Reilly and Moulty Fulmer would think of the heaps and heaps of gear we unload every night. Or what they would think of a trip blog.

Friday, March 23 Note: Yesterday's rigorous empirical testing confirms that you can immerse a flash drive in 47-degree water and it will still work. It's 6:22 a.m.--Daylight here in the canyon, even on a small beach tucked in beneath steep cliffs, and people are beginning to stir. There's the clank of pots and pans as the breakfast crew begins their work, a few quiet voices, and the sound of the river as it ripples and splashes along a rocky riffle along the shore. My tent is set up in a rocky cove at the very base of the tall red cliffs that ring the camp, and I have the Grand Canyon for a front porch. Last night, just before I stumbled into my tent after a day that felt much longer than the ten river miles we rowed, I joined Norm Takasugawa and Craig Wolfson on the beach. These guys know rivers, and have run Grand Canyon dozens of times. At the pre-launch dinner I asked Norm what he does in real life, when he's not being a river rat. "I'm a bum," he told me. Which, though probably not strictly true (I haven't seen anyone on the trip work harder than Norm), has given him a lot of time on the Colorado. Norm has been our sweep boat, the last man down the river. It's his job to solve any problems that the rest of us run into, fish us out of the water when we flip, help us to safety. Craig, I find out, used to be a competitive waterski racer. Probably not the kind of racing you're thinking of, though. Craig has hit 102 mile per hour on skis, behind a 21-foot boat with 1800 horsepower, and he and his wife Pam (she learned to ski at age 5) have both skied the Grand National Catalina Ski Race, about 50 miles out to California's Catalina Islands and back. Open ocean. On one ski. "It's much easier that way," Craig tells me. "Less friction." Dave Perez, another of the first-time rowers on the trip, asks him what's the fastest Craig ever crashed at. "About 90," Craig says. As in miles per hour. "What's that feel like?" I ask. "Concrete," he says. "When you're going that fast, you don't penetrate the water. You just keep skipping across the water until you get to about 60 miles per hour. Then you go under." He shrugs. "I moved on to safer things. Like motorcycle racing in the desert." Last night Norm and Craig were talking about House Rock Rapid. It's one that gets their attention even now, after countless runs through the Canyon (either that, or they were talking it up to scare the new guy). You enter on river left and have to row hard across the current to avoid getting swept into a horrendous mess of something or other--I'm not sure what, but it sounds ugly: a giant hole that will swallow an 18-foot raft? A mass of boulders to wrap a boat around? A whirlpool to suck you under? Whatever it is, I'll be rowing HARD across the current. And it still may not be enough. Meanwhile, if you go too deep with your downstream oar, it's likely to hit a rock that will pop it out of the oarlock to hammer your ribs or give you a knock-out blow to the jaw. Half the "fun" of a river trip, I suspect, is dread. I'm having lots of fun already. The Run At the top of a big rapid, you drift slowly downstream, standing up in your raft trying to spot something that looks familiar from when you scouted the rapid onshore. You have to find the right entry point, or you're screwed. Keep your raft sideways, broadside to the current, so you can quickly adjust position by rowing forward or back. And you wait, still trying to make sure. More waiting as the river slides you closer and closer. Moving a bit faster now as the water starts to drop into the rapid. Still waiting. "You've got all the time in the world," Tom Martin tells us. Too much time. That long slow drift to the lip where the world suddenly drops away is the worst of it. It's like a trip to the dentist--you know something is going to happen, but you're not sure how unpleasant it's going to be. Then when you're lined up, it's time to GO. In this rapid that means keeping your boat sideways, bow toward river left and rowing hard with the upstream oar to keep it that way. And you GO. Big waves that throw you around so hard that it's all you can do to keep hold of the oars. And the oars themselves yank you around, almost pulling you from your seat. But somehow you make it through the entry without going too far wrong. Keep rowing across the current, trying to stay away from whatever is waiting at river right. What's waiting at the bottom of House Rock Rapid on river right, it turns out, is a hole. I've heard people use that term before, but this is my first chance to see one. It's just what it sounds like--a circular spot in the river, maybe twelve feet in diameter, where the water level, for some arcane reason of hydraulics and flow and other I sweep by the House Rock hole at the end of my run, with my left oar close enough to touch its lip. Close enough for a good long look down into it. Either I got lucky, or I did something right in the big waves of the upper section. I'm starting to feel like a boatman. Then just downstream, in a smaller rapid that's nothing more than a couple of big waves, I'm almost hurled from my boat--only a tight grip on the oars keeps me aboard. I end up sprawled across the deck, trying to crawl back to my seat. Boulder Narrows Imagine a good-sized house set down in the middle of the river--that's Boulder Narrows. There's a thirty-foot-wide passage on either side. We stop here to film the five replica boats as they go past--three of them (the Susie R, the Flavell, and the Gem) duplicating their original 1957 high water trip, and two (Susie Too and the Portola) recreating a 1962 run--probably the last run of the wild river, as the gates of Glen Canyon Dam were shut later in the trip. More on that later. Meanwhike, lugging camera gear and tripods up the steep slopes is hard work. At our next stop I snap a photo of our videographer, Ian McCluskey, with a tripod in one hand and not one, but two cans of Pabst Blue Ribbon in the other. Today the rock at Boulder Narrows stands about twenty-five feet high above the river. There's a pile of driftwood on the top from the 1957 flood. When Moulty Fulmer and Pat Reilly ran this stretch at 100,000+ cubic feet per second, the rock was completely submerged.

Canyon Archeology Later in the day we stop to re-match photos from the 1957 trip. Here Tom Martin and Dave Mortenson have managed to identify one of Fulmer and Reilly's campsites. If you've seen the Canyon, you'll understand the enormity of that accomplishment. These guys have found the actual rock where Reilly and Fulmer set their coffee pot in 1957. They found their fire ring, with bits of charcoal buried under the sand. Reilly and Fulmer camped at the river side in 1957--you can see one of their boats in a photo from this spot, in front of a distinctive boulder. If you were to park a boat here today, you'd have to drag it up steep slopes and dunes 75 yards from the river, and 50 feet up.

I ask Dave Mortenson how in the world he and Tom Martin managed to find this spot again, after 55 years. With a hell of a lot of work, it turns out. "I see a picture and I can kind of tell you where it is, based on the rock," Mortenson tells me. Depending on how far along the Canyon you are, you'll have different layers of rock exposed. From top to bottom: Kaibab Limestone, Toroweap Formation, Coconcino Sandstone, Hermit Shale-a distinctive dark red, the only layer I'm confident I can actually identify so far-the Supai Group, Redwall Limestone, Muav Limestone, layer on layer on layer, a giant geological slice through the eons. "So then you're looking at--we also have journals that they kept on the trip," Mortenson tells me. "They in their journals will say, 'We camped at river right' at mile such and such. You can't go by today's mileage, because it may be a little bit off. But it gets you close." Close enough to find a 6-inch fire ring in a canyon almost 300 miles long. "We have visual clues and we have known clues, and you try to put that together," Mortenson says. "It's Sherlock Holmes stuff, you know?" Tom Martin, who wrote the book that I stole the description of Canyon geology from earlier, did a lot of the leg work. From the journals and photos, he knew about where Reilly and Fulmer camped. Then he took the photos along on a river trip and stopped at a likely side canyon, one where the Supai Sandstone was exposed, and seemed to match the photos. Close, but not close enough. It had to be a side canyon a little upstream, Tom decided. But since there's no rowing a heavy boat upstream, and you can only get one Grand Canyon permit per year, Tom had to wait until his next trip to find out for sure. Another year. The search, for a historian like Tom Martin, is an obsession that can't be denied. The Canyon seems to have that effect on people who know it. Thursday, March 22 Up before the sun, at 5:30. Not too many people stirring yet. A few birds chirping, the sky just light enough to see by, the quiet rush of the water flowing past. The plan is for the kitchen crew to be up at 6:30, with coffee call for the rest at 7:00, giving us enough time to pack up our tents and gear before breakfast. The first day of re-packing the boats, Tom Martin tells us, will be slow--we'll be lucky to hit the water by 10 a.m. Thinking of the mountains of gear and the matrix of cam straps required, I mentally adjust Tom's prediction to 10:40 a.m. But then, time doesn't matter too much here anyway. The quiet morning is reminding me that it's been far too long since I've done a long trip in canyon country--and I've never done one in Grand Canyon. A perfect place to be. I can just hear the kitchen crew moving around, heating water, getting ready to serve breakfast. A good time to tell you a bit more about the boats. Moulty Fulmer's Gem Of the five historic boats represented by replicas on this trip, Moulty Fulmer's Gem was the first one built, in 1953. Unlike Norm Nevills's 1940s cataract boats, Gem is based on a McKenzie River dory hull. When Moulty Fulmer first saw a McKenzie river boat, he knew it was something that could handle the big water of Grand Canyon. Strong rocker for maneuverability in fast water, flared sides for stability and buoyancy, it almost seemed meant for the rapids of the Colorado--and with the addition of decks fore and aft, and big buoyancy chambers bow and stern, Fulmer had his boat. Built in 1953 out of plywood, Gem was launched in 1954, and went on to run Grand Canyon for years, the first dory design on the Colorado. If you run into a hard boat on the Colorado today, its pedigree starts here, with Moulty Fulmer's Gem.

The replica Gem on our trip was built by Tom Martin. In the process, Tom discovered the reason for Gem's tiny transom (a true McKenzie River dory is a double ender):Gem's hull is so short and fat that Moulty Fulmer wasn't able to bend the plywood hull panels in far enough to make the double-ender Fulmer had hoped for. Still, with its banana-like rocker, both ends of the boat are out of the water anyway, and nothing was lost with the addition of a transom. Badger Creek Rapid Badger Creek Rapid, like most of the rapids we'll run, is the result of debris flushed into the Colorado River from an intersecting side canyon--two of them, actually. Look at Badger Creek Rapid from above and you'll see the shape of a cross, with the main Colorado running generally southward between tall cliffs, and two tributaries (Jackson Creek on river left, and Canyon Creek on River right) crossing at the same point. The boulders and debris washed down these tributary creeks chokes off the Colorado, forcing it to splash and surge its way over the obstacles. Those constrictions create the standing waves, whirlpools, eddies, holes, and drops that we'll have to find a way through. Right-side up, with luck. Besides giving us our first real chance to film the replica boats in action, today will be my first test at the oars of my raft. Badger Creek, at river mile 8 (our launch point at Lee's Ferry was mile 0), is the first real rapid we'll face. It's a 15' drop in about 1/6 of a mile, and is rated 5 out of 10 for difficulty. We'll see... Finally, don't be misled by the detail I'm providing here about the rapid. If it sounds like I know what I'm talking about, that's because I've stolen the information from the fourth edition of RiverMaps' Guide to the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon--a collection of topographic maps that covers the river from Lee's Ferry to South Cove. Tom Martin (with co-author Duwain Whitis) wrote it. So the information is his; the mistakes (I'm sure there will be some) are mine. Now I'm off to pack up my tent and gear, and maybe have enough time left over to explore a ways up Seven Mile Draw (which empties into the river here at Six Mile Camp, at river mile 6-- go figure) before we launch. The Day's Run Badger Creek Rapid, it turns out, is fairly idiot-proof. Line yourself up at the center as you begin and the river takes you where you want to be--which is definitely not always the case. Still, the veteran river runners on the trip agree that Grand Canyon whitewater tends to be like that. The trick is knowing where to start each run. After the rapid we stop for lunch, and to re-match a photo from the 1957 trip. Here Moulty Fulmer, Brick Mortenson, Pat Reilly, and Dwayne Norton stopped to discuss their strategy for the high water. Dave Mortenson has a photo of the four men gathered around a boulder, considering their strategy for the extremely high water they were facing that year. Dave calls for volunteers to re-stage the photo, and thanks to my floppy hat I get to play Pat Reilly. A few minutes of adjusting poses ("sit taller." "can you straighten your arm?"), a few photos, and the rematch is done.

The rest of the day is flat water and small ripples we don't bother to scout. The flat water is deceiving, though, because "downstream," it turns out, is largely a myth. The river goes where it wants to go, and unless you have an eye for the right line, you'll find yourself rowing upstream as the water swirls and eddies. There are subtle clues that let the trips good rowers keep moving fast just by positioning their boats in the right place. It's a knack I'm determined to pick up for myself. I don't have it yet. I've been rowing harder than the good boatmen, with less to show for it. We're behind schedule by afternoon, and stop to discuss whether we'll end the day by running House Rock Rapid today as originally planned. Boat after boat, though, comes in ready to camp here, above the rapid. It's been a long day for everyone: filming Badger Creek Rapid, re-matching photos, and for us beginners, learning to read the river so we can keep up on the flat water. We're all happy to camp. After finishing the dinner dishes (it's my team's duty night), I'm headed for bed at 9 p.m. Tomorrow we'll start with House Rock Rapid. Wednesday, March 21 We've had an easy day for my introduction to Grand Canyon river running. After spending yesterday moving mountains of gear (dry bags, ammo cans, more dry bags, more ammo cans, rocket boxes, kitchen boxes, propane tanks, food, more food, more dry bags, along with piles of every other conceivable waterproof container) onto the boats and lashing them down with cam straps, buckles, more straps (four-footers, six-footers, nine-footers, an overwhelming tangle of straps for every single item in each boat, each strapped down tightly in two directions until each raft seems little more than an intricate geometry of webbing in the shape of a boat), we shove off from Lee's Ferry after lunch. Sunny weather, blue skies, and temperatures in the 70s. Perfect.

Immediately after launching, we hit our first "rapids" a tiny set of ripples just downstream. Not much trouble even for me, but I‚m finding out that a fully loaded raft is a pig to row (think of riding a hippopotamus that hasn't been completely saddlebroken), and the river is powerful enough that it seems I'll have to learn to plan several moves ahead in fast water. I don't have the feel of it yet. Later in the day, in another set of tiny ripples, I misjudge the current and am almost swept onto a rock. Only a few frantic pulls with the oars keeps me off the rock. That'd be a heck of a way to start, breaking an oar or flipping a raft a mile out of camp. On a rapid a six-year-old could run.

After those first few ripples, the rest of the day is flat water between a narrow canyon formed by towering red-gold cliffs, and we'll be in camp by late afternoon, a sandy beach where a side canyon cuts through the cliffs on river right (facing downstream). It doesn't take too long to unload the boats and set up my tent, and I'm off for a scramble up a boulderfield, onto a steep scree bench high above camp. By the time I get back, supper is ready: salmon, rice, and Oreo cheesecake. And someone has even brought a camp chair for me. It'll be interesting to see if this gear-intensive luxurious style of camping corrupts me, changes my dirtbag backpacker habits. Probably not; I'm too lazy to haul all this gear unless I'm forced to do it. I'm learning as I go, and I'm in good hands. Most of the group has done Canyon trips before. Tom Martin, for example, has done many runs and hikes here, and has written or co-written guidebooks for Grand Canyon river runners and hikers. Tom is tall and lean, well over six feet, with gray hair, a mustache, and the soft-spoken, laid-back and uber-competent demeanor you'd expect from a veteran river rat. And he may not even be the most experienced boatman on the trip. "How many times have you done this trip, Tom?"I ask him as he's fiddling with some kind of hot drink for the campfire. "I don't know," he says. "I stopped counting when I passed my age." It was Tom who gave us our initial safety briefing: man overboard procedures, hand signals, everything that you need to know on big whitewater. He clearly knows what he's doing here, and yet has no doubts about us novice rowers being able to handle the trip. Which inspires confidence, with plenty of big rapids coming up and the water a chilly 47 degrees. But according to Tom and his wife Hazel, the biggest risk on the trip was the drive up from Flagstaff. Our culture has trained us to ignore the dangers of driving, while over-emphasizing the chance of serious trouble on the river. Still, whitewater safety, how to run rapids; that's important stuff. But after supper Tom Martin calls the novices together for something even more important: the groover talk. A groover, it turns out, is a toilet seat perched atop an ammo can. Carried for obvious purposes. Park regulations these days apparently require river runners to pack everything out. (Everything). We've got eight of these sealable ammo cans along, and a rotating assignment for a crew in charge of setting them up (not bad) and re-packing them (probably worse, especially as the trip goes on). Sixteen people. Twenty-four days. We'll have to stretch each can to three days. Which is why, beside the groover, is an orange bucket labeled "Pee." Separation of functions, Tom explains it. If people pee in the groover, it'll fill up too quickly. Instead, pee in the bucket, or in the river, the only other authorized option. Then do your business in the groover. Set here on the beach of Six Mile Camp, the groover makes up for it lack of amenities with a million-dollar view. Tomorrow brings our first real rapids. We'll see how it goes. I'm off to the campfire. Tuesday, March 20 Six months ago I had the good luck to meet Dave Mortenson, who has introduced me to an entire world of river runners, canyoneers, and yes, boat builders, a group that spans the decades from the 1940s to today. Norm Nevills. Moulty Fulmer. Brick Mortenson. P. T. (aka Pat) Reilly. Men mixed up in the beginning of modern Grand Canyon river trips and the origins of the dory-based whitewater boats still used to run the river even now. Mortenson and his friends know the history of Grand Canyon river running—they’ve lived it, told stories about those days, written books and made films about the early river runners. And those early trips! It’s tempting to think of the past as a Golden Age, easy to romanticize things and forget the advantages of our own time. I’m certainly guilty of that; modernity seldom suits me, with its rejection of the real world—the one I want to live in—and its proselytizing enthusiasm for the digital and online replacements that threaten to overwhelm us. But if there is such a thing as a Golden Age, the 1940s and 1950s was probably it for Grand Canyon river rats. These were men—and women—who ran the river with a degree of self-sufficiency that would be an anachronism in today’s world of cell phones and GPS. They designed and built their own boats, dragged them to the river on rutted tracks that deserved the label of “road” only at the best of times, and when they ran into trouble on the river, they got themselves out of it. And now, thanks to the river runners and boat builders that I’ve started to meet through Dave Mortenson, the boats of the 1950s are returning to Grand Canyon. 2011 saw three replicas of 1950s boats run Grand Canyon; this spring will see five replicas of 1950s and 60s boats on the river.

So, this blog: a record of a trip through Grand Canyon, in boats first designed and built by Moulty Fulmer and Pat Reilly in the 1950s and 60s. We’ll follow in their wake, camping where they camped, matching their photos with the river today. Along the way you’ll meet the boats, the people who built them, and, I hope, get some sense of what it’s like to run the Colorado River these days from the perspective of someone (me) who’s never done anything like it before. Twenty-four days and almost three hundred miles on the river, chasing ghosts in Grand Canyon. We’ll try to post a new update every day—but, canyons being what they are, that may not always be possible. We’ll do our best. Meanwhile, you can find out more about the Grand Canyon scene and the history of river running, along with pictures and video clips of the boats you’ll meet in this blog, at: https://www.historicriverboatsafloat.org// *** |

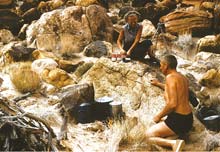

Moulty Fulmer (leading, in his Gem) and Brick Mortenson (Dave's father, rowing Reilly's Flavell) launch on their 1957 trip. On this run, Fulmer, Reilly, and Mortenson encountered the highest water ever run, cresting at 122,000 cubic feet per second. (Flows of 25,000 cubic feet per second are considered extreme high water today, with 7-12,000 closer to the norm). The water was so high in 1957 that the road to Lee's Ferry was flooded, and the boaters had to put in on from the flooded Paria River just downstream, pictured here.

Moulty Fulmer (leading, in his Gem) and Brick Mortenson (Dave's father, rowing Reilly's Flavell) launch on their 1957 trip. On this run, Fulmer, Reilly, and Mortenson encountered the highest water ever run, cresting at 122,000 cubic feet per second. (Flows of 25,000 cubic feet per second are considered extreme high water today, with 7-12,000 closer to the norm). The water was so high in 1957 that the road to Lee's Ferry was flooded, and the boaters had to put in on from the flooded Paria River just downstream, pictured here.